After years of schooling to become a medical entomologist, Dr. Hieronymo (Ron) Masendu (below), technical manager for the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) VectorLink Project in Zimbabwe, recently returned to the classroom to facilitate an entomological capacity strengthening training for Africa University (AU) staff.

In Zimbabwe, there are few experienced entomologists working on malaria. These specialists study and work to control the mosquitoes that transmit malaria, and play a critical role as the country moves towards malaria elimination. One of the major obstacles to ending malaria is mosquitoes’ ability to develop resistance to insecticides that previously killed them. So, monitoring mosquitoes is necessary to discover when and how resistance develops to better understand how to overcome it. In addition, accurate and up-to date information on malaria-carrying mosquitoes—such as which mosquito species carry the malaria parasite, where they are located, and what insecticides will be most effective to control them—helps Zimbabwe’s National Malaria Control Program (NMCP) and other stakeholders decide how to deploy interventions for malaria control and elimination, including outbreak situations. To strengthen local capacity, Dr. Masendu, in collaboration with AU’s PMI-funded Zimbabwe Entomology Support in Malaria Programme (ZENTO) project, a partner of the NMCP, organized a two-day training on insecticide resistance monitoring and species identification of Anopheles mosquitoes.

PMI VectorLink Zimbabwe has worked in partnership with AU since 2017, strengthening the skills of AU staff; procuring entomological materials, supplies, and equipment; and helping to construct a state-of-the-art Malaria Research and Reference Insectary on the AU campus. This partnership has, in turn, helped to strengthen the NMCP’s preparedness and response to malaria. The NMCP’s evidence-based decisions have been informed by AU’s knowledge of the mosquitoes that transmit the disease. AU analyzes mosquitoes that PMI VectorLink and the NMCP collect and is able to identify different mosquito species, confirming the initial species identification done by PMI VectorLink Zimbabwe. However, the AU team lacks the ability to conduct tests for insecticide resistance. Dr. Masendu’s training was geared to fill that gap.

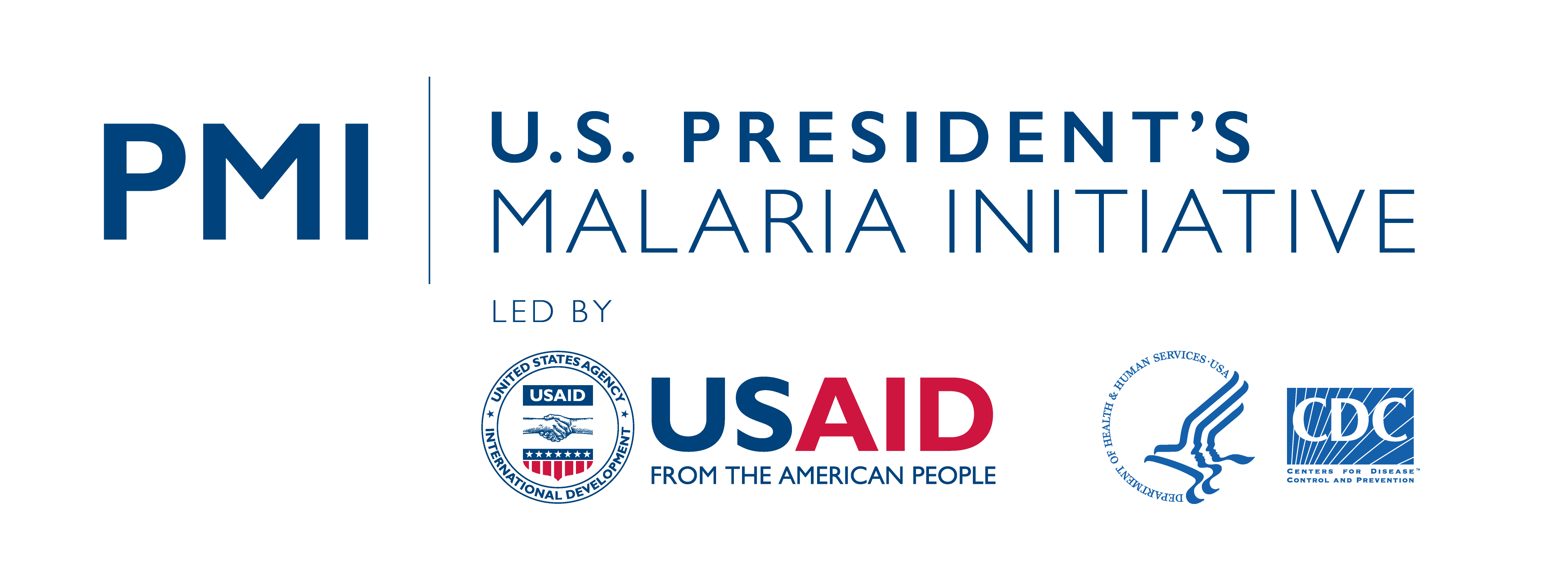

Six AU staff members attended the insecticide resistance monitoring training: one insectary manager, two laboratory assistants, one district coordinator for the ZENTO project, and two interns from AU. The training covered two insecticide resistance test methods—CDC bottle bioassay, the method PMI VectorLink Zimbabwe uses, as well as the widely used WHO tube test. Dr. Masendu started the training with background on recent gains in malaria control and the major threats to control and elimination globally. He then reviewed the theory behind the insecticide resistance testing methods before moving to practical sessions, in which participants practiced conducting CDC bottle bioassay and WHO tube tests with live, non-infected mosquitoes collected from the insectary on campus.

Photo Credit: PMI VectorLink Zimbabwe Technical Manager, Dr. Ron Masendu

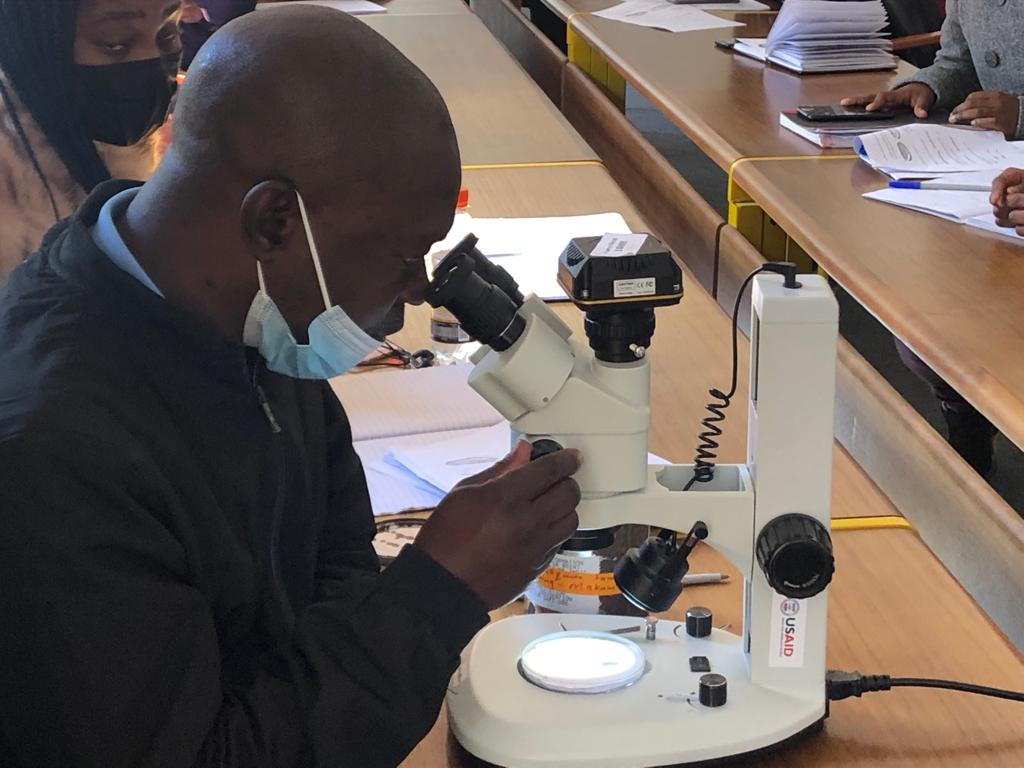

Fourteen people attended the mosquito species identification training, some of whom had attended the insecticide resistance monitoring training. One insectary manager, three laboratory scientists, three laboratory assistants, six laboratory interns and one project coordinator for the International Centers of Excellence for Malaria Research learned how to identify Anopheles mosquitoes using standard morphological identification keys, which identify different species of mosquitoes. Mosquito morphology deals with the form and structure of mosquitoes, focusing on visible features. This is an essential preliminary step in mosquito monitoring that helps save time in the laboratory.

“Most [participants] had no previous knowledge of using identification keys. It was also apparent most of the participants were not familiar with the terminology of the mosquito body parts that is essential in identification,” shared Dr. Masendu.

Using illustrations, the class discussed the terms and body parts used for species identification: the head, the thorax (midsection), and the abdomen of adult mosquitoes. Participants then viewed preserved mosquito specimens under a microscope, referencing the identification keys to categorize the mosquitos, and then practiced analyzing and identifying several specimens to test their knowledge.

Photo Credit: PMI VectorLink Zimbabwe Technical Manager, Dr. Ron Masendu

The training was well-received by its participants.

“Even though I did participate in an entomology training workshop a few years ago, it was very helpful to go through this two-day capacity-building training with Dr. Masendu,” stated Wietske Mushonga, a lab scientist at AU. “Our group was mixed, with some of us already having some entomology work experience, and others who did not have any. Dr. Masendu was able to take the time to give attention to everyone.”

By the end of the training, all participants were able to identify different species of mosquitoes and test for insecticide resistance using standard operating procedures, expanding the number of AU staff who can contribute to this work. Increasing the number of staff who can accurately identify different mosquito species will also reduce potential bottlenecks in analysis. Before the training, only three AU staff could conduct morphological identifications, now four more can with continued practice and guidance from their colleagues. While AU does not currently conduct insecticide resistance tests, they can now do so with guidance from PMI VectorLink Zimbabwe.

Dr. Masendu is optimistic about the future of AU’s entomological capacity. He stated that “strengthening staff knowledge of mosquito identification will help position AU to further build capacity in medical entomology at the national and regional level especially in morphological identification of mosquitoes that spread disease.”