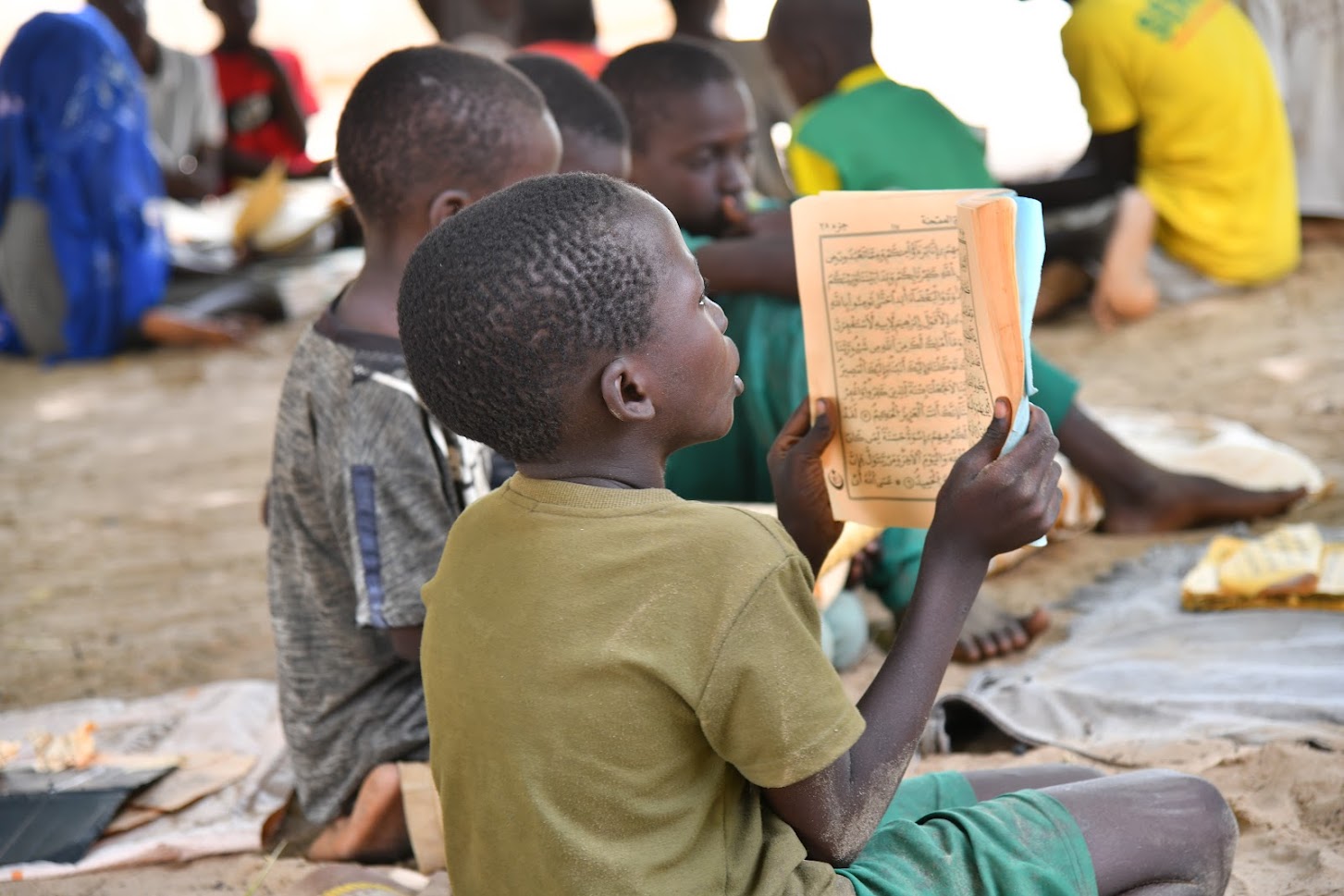

Despite progress in scaling up malaria control interventions, children in Sub-Saharan Africa are still largely impacted by the disease. Gaps in the distribution of mosquito nets are a contributing factor to children’s vulnerability. In Senegal, among the groups often unreached by formal distribution channels are youth living in religious schools that teach the Koran.

Students who attend these schools, called daaras, are usually boys ages 7 to 15 who are known as talibé children. Many come from families mostly in rural areas. According to Dr. Amdy Thiam, vector control lead for Senegal’s National Malaria Control Program (NMCP), the number of daaras and the talibé children that live in them are not well documented. In 2022, to fill in the knowledge gap, the NMCP, through trained community members, launched a census among religious and education leaders in the Thies region, where many of these schools are located, to determine the number of children living in daaras.

Although talibé children are eligible to receive insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) during the mass distributions that are conducted every three years in Senegal, the 2022 mass campaign excluded the Thies region due to limited government resources. These children are not eligible to access ITNs through other means such as routine distribution at health facilities that target pregnant women and children under five. Nor do daaras have the financial resources to purchase ITNs for their students.

To address these gaps, PMI VectorLink Senegal, in coordination with the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health and Social Action through the NMCP, planned to reach talibé children via a pilot project which distributed ITNs at no-cost to daaras in the health district of Tivaouane, one of the nine districts in the Thies Region. Tivaouane health district has more than 200 daaras, home to approximately 50 talibé children per daara.

“Financial barriers are the main obstacles to vector control through ITNs in most daaras,” stated PMI VectorLink Senegal’s Abdul-Aziz Mbaye, who manages ITN distribution for the project, noting that in the few daaras where ITNs were available, there were not enough. Of the ITNs that were present, many were worn, with holes and insecticide that was likely no longer effective.

Providing nets to the daaras was the first step. The next challenge was to adapt to the non-traditional sleeping quarters found in most of these schools. In most daaras, there are no regular beds. Children sleep on mattresses or mats on the floor, and three to five children often share one mattress. In some cases, the ITN size was smaller than the dedicated sleeping places. To help address this, VectorLink Senegal provided samples of merged ITNs (made by sewing together two ITNs to increase the size) to cover sleeping places of more than four talibé children. The daaras can replicate this model using local tailors but the pilot project showed that less than 20% of daaras merged the ITNs.

Another challenge is that many dormitories also serve as classrooms, with this multipurpose usage a barrier to the consistent use of bed nets. Mbaye shared that “the multiple uses [of rooms] prevent the permanent hanging of ITNs in the sleeping areas. To address this, daaras leadership requested support to acquire materials for the permanent hanging of ITNs in multi-purpose rooms.

To further promote proper and consistent use of ITNs, PMI VectorLink Senegal, the NMCP, regional and district health officials, and daaras’ leadership developed posters in French, Arabic, and Wolof (written using the Arabic alphabet), the local language, and placed them in each daara that received ITNs. The posters focused on the advantages of using ITNs while sleeping, and how to properly hang a net.

In total, PMI VectorLink Senegal and the NMCP distributed 7,312 ITNs to 237 daaras in August 2022, protecting 12,246 talibé children. When PMI VectorLink Senegal and the NMCP returned one month later to monitor the hanging of the nets, they found that in the daaras visited (89 percent), 82 percent of the ITNs distributed were hung, and all the talibé children at those daaras were sleeping under an ITN every night. The project’s close partnership with daaras’ leadership and the involvement of other local authorities responsible for governing and regulations concerning education and training in all aspects of planning and execution led to the successful implementation of the pilot.

Dr. Thiam stated that the NMCP will review the lessons learned from the pilot, and PMI VectorLink Senegal also identified points for improvement. For example, if there are future distributions (which the NMCP and PMI have yet to decide), the NMCP and its partners should perhaps share responsibility with daaras for merging ITNs.

This pilot can help fill gaps in access to ITNs and eliminate barriers to proper and consistent use. Advancing equity in access moves Senegal towards its goal of achieving malaria elimination by 2030.