Mozambique

Duartina Francisco serves as Country Operations Director and Gender Focal Person for the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) VectorLink (VL) Project in Mozambique. She began working in vector control with the PMI Africa Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS) Project in 2012. Duartina holds an MBA in Management of Integrated Systems, Quality Environment and Safety from Mozambique’s Higher Institute of Science and Technology and a Bachelor in Environment Management, Planning and Community Development. She’s a trained nurse in maternal and infant health and previously worked as a field officer and trainer on a project that focused on orphans and people living with HIV. Recently, Duartina took time out of her busy day to talk about her work.

Duartina Francisco serves as Country Operations Director and Gender Focal Person for the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI) VectorLink (VL) Project in Mozambique. She began working in vector control with the PMI Africa Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS) Project in 2012. Duartina holds an MBA in Management of Integrated Systems, Quality Environment and Safety from Mozambique’s Higher Institute of Science and Technology and a Bachelor in Environment Management, Planning and Community Development. She’s a trained nurse in maternal and infant health and previously worked as a field officer and trainer on a project that focused on orphans and people living with HIV. Recently, Duartina took time out of her busy day to talk about her work.

What do you find most challenging about your job?

Convincing and mobilizing targeted populations to accept having their houses sprayed is the most challenging aspect (IRS involves spraying the inside walls and ceilings with an insecticide that kills the malaria parasite-carrying mosquitoes). There are lots of myths about IRS that make it challenging for people to accept IRS. The most recent widespread myth was that IRS spray operators were vampires and that mobilizers were marking houses to easily identify which households would have their blood sucked. This caused many households to remove all mobilization stickers and to wipe off any markings that mobilizers left on their houses as part of the house-to-house mobilization. IRS requires the entire community’s acceptance and efforts (The World Health Organization recommends higher than 85 percent coverage for IRS to be successful).

In Mozambique, community leaders are also political leaders and play a critical role in IRS. They are responsible for encouraging their community to stay at home and not to leave to farm on spray days so that they can have their houses sprayed. By involving local leaders before the IRS campaign began, we were able to dispel this myth.

Another challenge has been the impact of natural disasters, such as heavy rains and cyclones. While malaria incidence has decreased thanks to the project’s vector control interventions, the flooding and rains provide additional breeding grounds for mosquitoes, which results in higher abundance of mosquitoes and increased risk of malaria transmission.

What changes have you seen in IRS implementation since the PMI VectorLink Project began?

There has been an increase in the engagement of political leaders at all levels in malaria matters, especially for IRS. We have many political parties in country. In the past, it was difficult for a member of the opposition party to accept IRS because they saw it as political issue and not a health issue. This resulted in many refusals for spray in communities that were known to be affiliated with the opposition party. The project began having separate, focused meetings at both the provincial and local levels within the community structure to ensure that all political party leaders are involved in IRS. There used to be one central level meeting where leaders of the opposition political parties were not invited or represented. Once the meeting moved to different levels, it improved participation from all leaders.

How does the project reach the most vulnerable, particularly those not previously protected with vector control? Our target populations include those living in very remote places where it is difficult for them to reach basic health care services in time if they contract malaria and where there is little access to buy products to protect their houses against mosquitoes. We prioritize these areas for IRS first to ensure we reach them before it rains, when it becomes more difficult to travel. With the introduction of the IRS mobile soak pit, our work in remote areas is easier.

In IRS, spray operators rinse liquid waste from spray tanks and protective gear into soak pits that adsorb and safely degrade the traces of insecticide found in the wash-water. In most spray areas, soak pits are permanent installations in a central location that can be accessed at the end of the spray day. However, in some hard-to-reach areas, it is difficult and sometimes impossible for spray teams to return to a soak pit for clean-up purposes. The mobile soak pit, developed under the PMI Africa Indoor Residual Spraying Project, can be carried to a spray location, installed at a wash site in minutes, and used to catch and treat insecticide waste. When spray operations in the area are complete, the soak pit is dug-up and carried away for use at the next location, while the site is restored to its original condition.) We shared this innovation with other provinces, and they are using it, too, which helps us to ensure we don’t leave anyone behind.

Since the project began there has been a decrease in mortality from malaria. The reduction in malaria prevalence in Zambezia Province (where the project implements IRS) went from 68% to 44% between 2015 and 2018 in children under 5 years[1]. At the Zambezia’s 2021 malaria provincial evaluation meeting, the Provincial Health Directorate reported a 9.1% reduction in malaria-related deaths in its eight-month Zambezia malaria progress report in the districts that receive IRS and insecticide-treated nets.

How does the project invest in local partners to lead malaria programs?

The project engages local partners to lead programs by sharing best practices in managing IRS activities. For instance, PMI VectorLink was the first project in the country to use checklists to supervise IRS activities. This best practice was adopted by the National Malaria Control Program (NMCP) and recommended to all partners to monitor IRS. The project also introduced the best practice of using the mobile soak pit in hard-to-reach areas, which is now being used by the government in three provinces.

Heads of health posts, malaria focal point persons, environmental health officers, among others from the Ministry of Health, have received training from the project. These staff have gone on to train government spray operators who are now capable of supervising spray campaigns. Our project checklists also have been adopted by the Ministry of Health and other partners to manage the entire malaria program, including monitoring malaria indicators at the country level. The VL environmental compliance checklist was adopted and used as foundation for the NMCP, not only for IRS but all malaria strategies implemented in the country. The government’s training of trainers’ curricula was also adjusted based on the project’s curricula. This impact has been very notable as the project is a model for IRS implementation in three regions of the country.

The project also provides entomology support to six provinces, including Zambezia where the project implements IRS. The reported entomological data helps the National Malaria Control Program to make informed vector control decisions for areas where the malaria incidence is increasing.

What progress have you seen in gender equity as Gender Focal Person?

In 2015, when the AIRS Project began to actively promote gender equity and female empowerment at all levels of IRS operations, it seemed like an impossible task to achieve. We started with 7% female participation in IRS. Now we are at 33%. Apart from numbers, I have seen many women apply for different positions (that have traditionally been held by men), such as drivers, spray technicians, site supervisors, and team leaders. At the beginning of the project, women were predominantly working as washers with some working as spray operators. So there has been very good progress, and I am very happy to be part of that.

Can you talk about how the project supports systems to be resilient against the COVID-19 pandemic and other shocks?

Running the vector control activities during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has been a challenge. The PMI VectorLink Project works across 26 countries to protect people from malaria. With such a big project, there is diversity of ideas, contexts, and challenges. We learned lessons from other countries that sprayed under the pandemic before Mozambique. As a result, we adjusted our operating procedures, and with Mozambique’s Ministry of Health (MOH) guidance, we developed an action plan to ensure to minimize the spread of COVID-19 among the team. Continuous sharing of information and experiences will contribute to the project being resilient against pandemics and other shocks in the future.

Do you think Mozambique will ever be malaria-free?

Yes, by continuing to implement integrated vector control and management strategies, it can be. There are many interventions taking place at the national level, such as housing improvement, environment sanitization, and massive distribution of bed nets. The integrated vector control management model has shown progress towards elimination in the southern part of the country, which was declared to be in the malaria elimination phase by Southern Africa Development Community in 2020. My hope is that the NMCP continues making efforts in the adaptation/adoption of the tools and best practices used under VL to fight malaria and to expand IRS to other provinces, since the whole country is endemic for malaria.

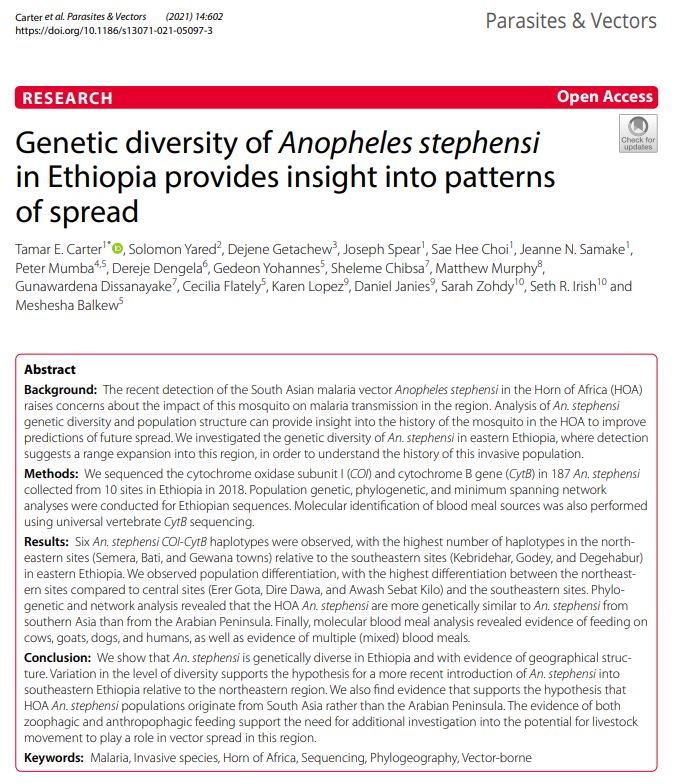

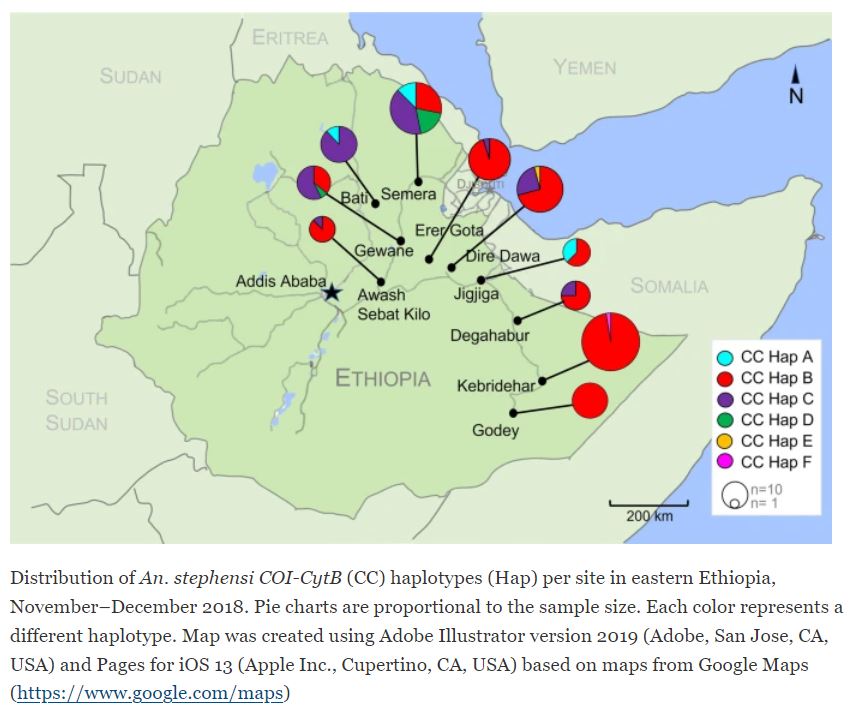

The detection of the Asian malaria vector Anopheles stephensi in the Horn of Africa (HOA) more than 10 years ago has caused growing concern among malaria stakeholders about the invasive vector’s potential to spread malaria and the effect the vector could have on sustaining gains in malaria control in the region. In 2019, the World Health Organization identified An. stephensi as a “major potential threat” in the progress to control malaria and called for enhance surveillance in Africa.

The detection of the Asian malaria vector Anopheles stephensi in the Horn of Africa (HOA) more than 10 years ago has caused growing concern among malaria stakeholders about the invasive vector’s potential to spread malaria and the effect the vector could have on sustaining gains in malaria control in the region. In 2019, the World Health Organization identified An. stephensi as a “major potential threat” in the progress to control malaria and called for enhance surveillance in Africa.